Today, it emerged that the Trump administration is working to shut down NCAR, the National Centre for Atmospheric Research, one of the most important research centres in the world for meteorology, climate change, and the physics of our planet’s atmosphere. I wrote about NCAR’s work in my book, Computing the Climate, so I’m publishing here an extract on NCAR from that book, to help mark more than 60 years of world-leading research at the lab. This is from Chapter 6, The Well-Equipped Physics Lab.

The Mesa Lab

The city of Boulder nestles into the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. From the airport in Denver, the mountains appear as a dark ribbon on the horizon. In the hour it takes to drive up to Boulder, they gradually grow in size – by the time you reach the outskirts of Boulder, the mountains dominate every view. Up above Boulder, on a plateau overlooking the city, sit the bold salmon-coloured turrets of the Mesa Lab, the headquarters of the National Centre for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). The building was designed by the renowned architect I. M. Pei, who – inspired by the ancestral cliff dwellings of the Pueblo peoples – used a cubist design and salmon coloured concrete to give the impression it was carved out of the mountain.

Inside the lab, Pei wanted to create an interesting space for an inter-disciplinary group of scientists, to support the messy work typical of doing science. He designed the offices with lots of wall space for scientists to pin up notes and diagrams. Each office is a slightly different size, to allow for different needs. In each tower, a set of “crows nest” offices can be reached – each by its own spiral staircase – and these offices open out onto rooftop patios, where the scientists can step outside to think while they contemplate the amazing view. Throughout the building, the corridors twist and turn, to avoid any sense of repetition. This makes the building more interesting – and almost impossible for new visitors to find their way around without help.

In Boulder, virtually everyone embraces a mountain sport, so naturally there’s a steep hiking trail straight up the mountainside to the Mesa Lab and bike lanes on the long circuitous approach road. The lab sits a thousand feet higher than the city, so both routes involve working up a major sweat, and I find the air is noticeably thinner at the top. It takes me a few days to get acclimatized each time I visit, and I often have to stop for breath even just on the steps up from the parking lot. So, while I did manage the bike trail a few times, most mornings I used the free shuttle bus, which has plenty of bike racks, and enjoyed the long freewheel bike ride back down in the evenings.

NCAR is America’s leading centre for research on atmospheric sciences and climate change. Although it is funded primarily by the federal government, NCAR is not part of any federal agency. It’s purely a research lab – it doesn’t issue commercial weather forecasts, although it does have an excellent visitors’ centre. It’s funded primarily by the National Science Foundation, operated by a non-profit consortium of universities, and employs over 1,000 staff, of whom nearly half are scientists, along with another 150 technical and engineering support staff.

A Community Model

NCAR’s main climate model is known as the Community Earth System Model (CESM). As the name suggests, the model is intended as a resource for the broader scientific community. The scientists at NCAR offer regular training workshops for scientists who want to learn how to work with the model, and NCAR provides user support and detailed descriptions of the design of each version of the model. As a result, the model is probably the most widely used climate model in the world today.

It also has one of the longest pedigrees. Computational modelling of the atmosphere began at NCAR in 1963. While the first models worked only on NCAR’s computers, the intention was always to build a model that university-based researchers could run their own computational experiments on. This goal was reached in 1983, with the first public release of the Community Climate Model, offering the program code freely to anyone. At first, it was just a global atmosphere model, but it has undergone many improvements since then, with ocean, land and sea ice components added in the mid-1990s, and components to simulate glaciers, ocean waves, and rivers added more recently.

It isn’t strictly accurate to call CESM “NCAR’s model,” because many other labs contribute substantial effort to developing the model, and funding comes from a number of US federal agencies. Both the ocean model (known as POP, the Parallel Ocean Program) and the sea ice model (CICE, pronounced “C-ice”) were originally developed at Los Alamos National Labs. Ongoing improvements to all the component models are managed by teams of scientists with representatives from government labs and university research groups.

More than 300 scientists show up every June for an annual workshop to hear about new improvements to the model and its components, coordinate plans for future work, and to discuss the latest science being done with the model. These workshops were traditionally held in Breckenridge, high in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, although recently they’ve moved to a larger venue in Boulder itself. In the summer of 2010, I arrived at NCAR just in time to attend that year’s Breckenridge workshop, which gave me a rapid introduction to the community and how it works, and an opportunity to sit down with many of the lead scientists associated with CESM, and find out more about their work.

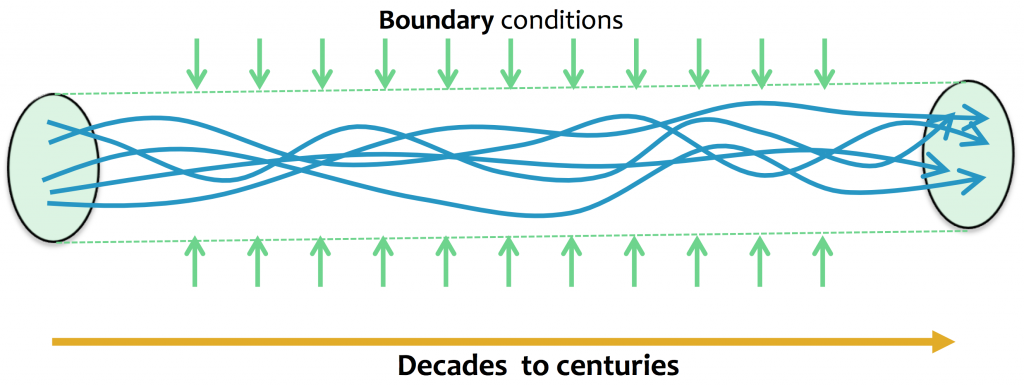

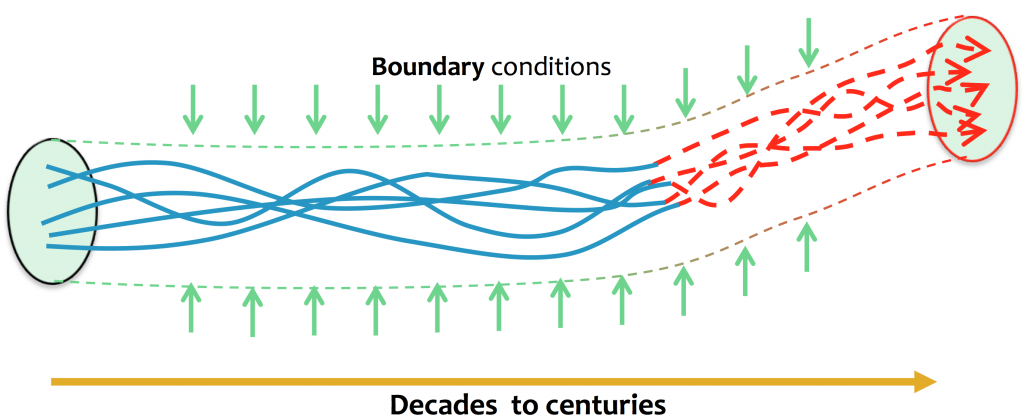

A Suite of Models

CESM is not really a single model. It’s an integrated modelling suite, with seven separate model components – atmosphere; oceans; ocean waves; land surfaces; rivers; land ice; and sea ice – each developed by its own community of experts. These component models each have their own community of users, who often just run their component on its own. Oceanographers might run ocean simulations without worrying about interaction with the atmosphere; glaciologists might run just the ice sheet model on its own to study the movement of glaciers, and so on. Climate scientists often move back and forth between running an individual component to study specific processes, and running CESM as a whole, to study what happens when those processes interact with other parts of the Earth system.

The host for my visits to NCAR was Mariana Vertenstein, manager of the CESM software engineering group, a team of a dozen scientists who support the various working groups to ensure the software for the models is well-designed and properly tested. Over the years, Mariana’s team has been responsible for transforming the component models that make up CESM from a disparate set of stand-alone models into an integrated modelling system. Mariana likens this approach to a well-equipped physics lab, with all the right equipment in place to do different kinds of experiments.

CESM weighs in at over a million lines of code, meaning considerable software engineering effort is required to coordinate the work of the community. But such effort is often invisible when it’s done well. So I was surprised and delighted when I arrived at the Breckenridge workshop in 2010, to learn that the community was awarding Mariana the annual CESM distinguished achievement award, an acknowledgement of both the central importance of good software engineering to scientific modelling, and the key role Mariana has played in managing the technical challenges of a large and complex engineering project.

A community model must also run on a wide variety of different machines. NCAR is unusual among climate modelling labs for designing the model to be relatively easy to port to different kinds of computers, and for guiding users across the world who want to run it on their own machines. When I visited in 2010, I noticed my own laptop, a MacBook Pro, was on the list of target machines, but wasn’t yet officially supported, which meant nobody had yet built and tested a version of CESM for it. I decided to try installing it myself. It took me a couple of days to get the code compiled and running before I had a successful test run on my laptop, largely because – like most modern scientific software – CESM is built on top of many existing scientific software packages, and I needed to make sure I had compatible versions of all these packages installed on my laptop first.

Of course, full-scale simulations of the climate in CESM would require a supercomputer. In the early days at NCAR, the supercomputers were housed in the basement of the Mesa Lab. But its needs have grown so much, it now operates a dedicated supercomputer facility in Wyoming. Two generations of its supercomputers are shown below. When it was first installed, NCAR’s latest supercomputer, Cheyenne, was ranked as the 20th fastest machine in the world.

Open Source

Most scientific software is developed by scientists themselves, for use in their own labs – tools for organizing and analyzing data from field studies, tools for displaying data and scientific results in different formats, and so on. Sometimes, a software tool used in one lab is useful to many other scientists, and the scientists who built it will often share it freely, making the code available on one of several popular code sharing websites. Occasionally, these tools acquire a broader community of users, who build upon the original tools, often evolving them into a large software libraries – suites of useful tools – that the scientific community comes to rely on. Shared software libraries simplify much of the grunt work in doing science, from working with raw data all the way through to preparing papers for publication.

The idea of open source software is very attractive to scientific communities. Making your program code available to anyone who wants to adapt and modify it to their own needs reflects a core value for most scientists. Science is a community endeavour, and scientists need other scientists to replicate their work, to check their results are valid, and to build on their contributions. But most science is done on a shoe-string budget, held together with a patchwork of grants from government agencies, which never have enough funding to go around. Scientists usually have very little budget to pay for specialized software tools, and the demand for such tools is often too small to support commercial companies trying to sell them. Freely sharing the software is usually the only approach that works.

The vast majority of open source software, however, turns out not to be useful to anyone other than the people who built it. A lot of the software on open source code sharing sites has, in effect, no community of users at all. A very small handful of projects have thousands of users, while thousands of projects have only a very small handful of users. In this context, CESM is clearly a runaway success. The few hundred scientists who come each year to the annual CESM workshop represent only the tip of an iceberg. Over 6,000 scientists have registered to download and use CESM, and the number is growing rapidly – in the last couple of years, this number grew by about 900 per year. Many of these users register so they can download and install CESM on a shared computing facility, where many other scientists will have access to it. The CESM online discussions groups regularly attract tens of thousands of participants.

It took a long time to grow a community of this size. By regularly publishing newer and better versions of the model, documenting its design in detail, and training new users, NCAR has established CESM as the preferred climate model for a large and disparate community of scientists – atmospheric physicists, oceanographers, paleoclimatologists, ecologists, glaciologists, marine biologists, environmental scientists, chemists, and more. These scientists use the model to study the climate of the distant past, to make sense of recent or current data on global environmental change, and to explore future scenarios of how the climate might be further affected by both human activities and natural processes.

As my book has now been published, it’s time to provide a little more detail. My goal in writing the book was to explain what climate models do, how they are built, and what they tell us. It’s intended to be very readable for a general audience, in the popular-science genre. The title is “Computing the Climate: How we know what we know about climate change”.

As my book has now been published, it’s time to provide a little more detail. My goal in writing the book was to explain what climate models do, how they are built, and what they tell us. It’s intended to be very readable for a general audience, in the popular-science genre. The title is “Computing the Climate: How we know what we know about climate change”.