In a blog post that was picked up by the Huffington post, Bill Gates writes about why we need innovation, not insulation. He sets up the piece as a choice of emphasis between two emissions targets: 30% reduction by 2025, and 80% reduction by 2050. He argues that the latter target is much more important, and hence we should focus on big R&D efforts to innovate our way to zero-carbon energy sources for transportation and power generation. In doing so, he pours scorn on energy conservation efforts, arguing, in effect, that they are a waste of time. Which means Bill Gates didn’t do his homework.

What matters is not some arbitrary target for any given year. What matters is the path we choose to get there. This is a prime example of the communications failure over climate change. Non-scientists don’t bother to learn the basic principles of climate science, and scientists completely fail to get the most important ideas across in a way that helps people make good judgements about strategy.

The key problem in climate change is not the actual emissions in any given year. It’s the cumulative emissions over time. The carbon we emit by burning fossil fuels doesn’t magically disappear. About half is absorbed by the oceans (making them more acidic). The rest cycles back and forth between the atmosphere and the biosphere, for centuries. And there is also tremendous lag in the system. The ocean warms up very slowly, so it take decades for the Earth to reach a new equilibrium temperature once concentrations in the atmosphere stabilize. This means even if we could immediately stop adding CO2 to the atmosphere today, the earth would keep warming for decades, and wouldn’t cool off again for centuries. It’s going to be tough adapting to the warming we’re already committed to. For every additional year that we fail to get emissions under control we compound the problem.

What does this mean for targets? It means that it matters much more how soon we get started on reducing emissions rather than eventual destination at any particular future year. Because any reduction in annual emissions achieved in the next few years means that we save that amount of emissions every year going forward. The longer we take to get the emissions under control, the harder we make the problem.

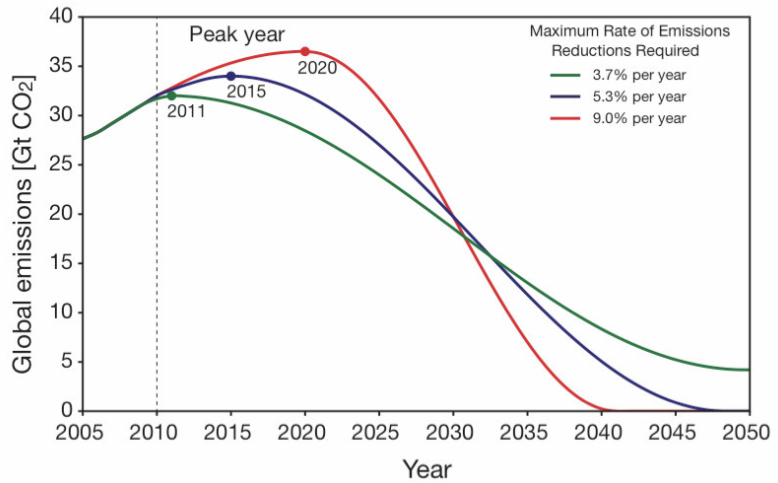

A picture might help:

Three different emissions pathways to give 67% chance of limiting global warming to 2ºC (From the Copenhagen Diagnosis, Figure 22)

The graph shows three different scenarios, each with the same cumulative emissions (i.e. the area under each curve is the same). If we get emissions to peak next year (the green line), it’s a lot easier to keep cumulative emissions under control. If we delay, and allow emissions to continue to rise until 2020, then we can forget about 80% reductions by 2050. We’ll have set ourselves the much tougher task of 100% emissions reductions by 2040!

The thing is, there are plenty of good analyses of how to achieve early emissions reductions by deploying existing technology. Anyone who argues we should put our hopes in some grand future R&D effort to invent new technologies clearly does not understand the climate science. Or perhaps can’t do calculus.

Hi Steve,

A good point, but Bill’s argument justifying innovation is wrong for another reason. There are simpler ways of understanding the climate change issue other than forcing it into a cumulative emissions framework.

The suitability of the environment is not a solely or even mostly a function of temperature. And the temperature is not nearly determined solely by CO2 emissions. Therefore, how could CO2 emissions be the determining parameter in either the probability or the magnitude of any climate insufficiency?

A better parameter? Why, population, of course.

George

[“forcing it into a cumulative emissions framework”??? Cumulative emissions (i.e. atmospheric concentrations) of GHGs *is* the problem. Your reasoning seems to be backwards – Steve]

Pingback: buzz

Most disturbing is to observe that Gates appears to be guided by marketing principles, not valid scientific advice. Asking for innovation without a grounding in the science is both deluded and risky.

The only compliment I can offer Gates is to say thanks for starting to look at the issue.

“he pours scorn on energy conservation efforts, arguing (effectively) that they are a waste of time.”

A niggling point: you might be better off saying “…arguing, in effect, that..” rather than having a reader assume that you meant that Gates was arguing effectively.

[Fixed. Many thanks! – Steve]

Pingback: Why we need to cut emissions today, not tomorrow » Mind of Dan

Steve, great post. I critiqued Gates from another angle here:

http://www.grist.org/article/2010-02-17-why-bill-gates-is-wrong-on-energy-and-climate

Pingback: Bathtubs, waistlines, and credit cards « Catenary

So, here’s the issue I have with your read on Bill Gates talk..

Through his work in the Foundation, he has repeatedly said that they will not contribute to projects that are “me too” efforts, or where there is already action underway. He considers it his moral duty to apply his considerable resources in arenas where people who don’t have the GDP of a small nation on tap simply cannot go.

I have watched the talk twice now, and I simply do not see what you see – I think that in this case, everyone is talking about reduction of emissions, and nobody is talking about how to get more energy than we have at present.

Energy is the magic bullet here – if we have abundant, reliable, clean energy then a whole range of applications open up – recycling materials like glass and metals uses a lot of energy. if we have lots of clean energy, electric cars, vans, buses become a no brainer.

Bill Gates is asking the question that needs to be asked – where is the replacement for oil energy coming from?

Far too many people in the green lobby are viewing Peak Oil as the end of inevitable end of industrial civilisation (and it seems that some of them are viewing this with a certain relish), when in reality, peak oil does not have to be any more significant a shift for us than Peak Hay, or Peak Horse.

When we have scientists telling us that TWRs could provide energy for the whole world at current US levels of usage, for close on a Millenia using only the nuclear waste currently stockpiled in the USA – and this is before we even look at Thorium – then it needs to be taken seriously.

Bill Gates is opening up a wing of the debate which has been sorely neglected. I really don’t think he is suggesting that the other stuff shouldn’t happen as well.

Ian: my piece was in response to his original blog post rather than the TED Talk. He originally titled his post “why we need innovation, not insulation”, and later (presumably on advice from his staffers) changed it to “why we need innovation as well as insulation”. There are plenty of roadmaps for how we get there with current technologies – the challenge is investment and deployment, not innovation. Whenever I hear people like Gates pin solutions to climate change on some future technological breakthrough, I’m reminded of people who rack up debt on their credit cards in the hope that they’ll one day win the lottery. We’re already paying compound interest, while we already have available the tools to dramatically reduce the debt.

We’ll make technological breakthroughs in the future with or without Gates’ help. But none of that is particularly relevant to what we need to be doing today.

Pingback: Ethics of Climate – Talk by Ray Pierrehumbert | Serendipity

One year later: Perhaps Bill Gates was just naïve.

Pingback: The different meanings of “Climate Sensitivity” | Serendipity

Pingback: Why we need to cut emissions today, not tomorrow | Mind of Dan