I’ve spent some time pondering why so many people seem unable or unwilling to understand the seriousness of climate change. Only half of all Americans understand that warming is happening because of our use of fossil fuels. And clearly many people still believe the science is equivocal. Having spent many hours arguing with denialists, I’ve come to the conclusion that they don’t approach climate change in a scientific way (even those who are trained as scientists), even though they often appear to engage in scientific discourse. Rather than assessing all the evidence and trying to understand the big picture, climate denialists start from their preferred conclusion and work backwards, selecting only the evidence that supports the conclusion.

But why? Why do so many people approach global warming in this manner? Previously I speculated that the Dunning-Kruger effect might explain some of this. This effect occurs when people at the lower end of the ability scale vastly overestimate their own competence. Combine this with the observation that few people really understand the basic system dynamics, for example that concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will continue to rise even if emissions are reduced, as long as the level of emissions (burning fossil fuels) exceeds the removal processes (e.g. sequestration by the oceans). The Dunning-Kruger effect suggests that people whose reasoning is based on faulty mental models are unlikely to realise it.

While incorrect mental models and overconfidence might explain some of the problem that people have in accepting the scale and urgency of the problem, it doesn’t really explain the argumentation style of climate denialists, particularly the way in which they latch onto anything that appears to be a weakness or an error in the science, while ignoring the vast majority of the evidence in the published literature.

However, a series of studies by Kahan, Braman and colleagues explain this behaviour very well. In investigating a key question in social epistemology, Kahan and Braman set out to study why strong political disagreements seem to persist in many areas of public policy, even in the face of clear evidence about the efficacy of certain policy choices. These studies reveal a process they term cultural cognition, by which people filter (scientific) evidence according to how well it fits their cultural orientation. The studies explore this phenomenon for contentious issues such as the death penalty, gun control and environmental protection, as well as issues that one might expect would be less contentious, such as immunization and nanotechology. It turns out that not only do people care about how well various public policies cohere with their existing cultural worldviews, but their beliefs about the empirical evidence are also derived from these cultural worldviews.

For example, in a large scale survey, they tested people’s attitudes to the perception of risks from global warming, gun ownership, nanotechnology and immunization. They assessed how well these perceptions correlate with a number of characteristics, including gender, education, income, political affiliation, and so on. While political party affiliation correlates well with attitudes on some of these issues, there was a generally stronger correlation across the board with the two dimensions of cultural values identified by Douglas and Wildavsky: ‘group’ and ‘grid’. The group dimension assesses whether people are more oriented towards individual needs (‘individualist’) or the needs of the group (‘communitarian’); and the grid dimension assesses whether people tend to believe societal roles should be well defined and differentiated (‘hierarchical’) or those who believe in more equality and less rigidity (‘egalitarian’).

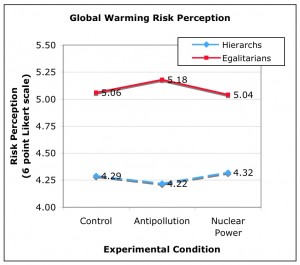

The most interesting part of the study, for me, is a an experiment on how perceptions change depending on how the risk of global warming is presented. About 500 subjects were given one of two different newspaper articles to read, both of which summarized the findings of a scientific report about the threat of climate change. In one version, the scientists were described as calling for anti-pollution regulations, while in the other, they were calling for investment in more nuclear power. Both these were compared with a control group who saw neither version of the report. Here are the results (adapted from Kahan et al, with a couple of corrections supplied by the authors):

In all cases, the mean risk assessment of the subjects correlates with their position on these dimensions: individualists and hierarchs are much less worried about global warming than communitarians and egalitarians. But more interestingly, the two different newspaper articles affect these perceptions in different ways. For the article that described scientists as calling for anti-pollution measures, people had quite opposite reactions: for communitarians and egalitarians, it increased their perception of the risk from global warming, but for individualists and hierarchs, it decreased their perception of the risk. When the same facts about the science are presented in an article that calls for more nuclear power, there is almost no effect. In other words, people assessed the facts in the report about climate change according to how well the policy prescription fits with their existing worldview.

There are some interesting consequences of this phenomenon. For example, Kahan and Braman argue that there is really no war over ideology in the US, just lots of people with well-established cultural worldviews, who simply decide what facts (scientific evidence) to believe based on these views. The culture war is therefore really a war over facts, not ideology.

The studies also suggest that certain political strategies are doomed to failure. For example, a common strategy when trying to resolve contentious political policy issues is to attempt to detach the policy question from political ideologies, and focus on the available evidence about the consequences of the policy. Kahan and Braman’s studies show this won’t work, because different cultural worldviews prevent people from agreeing what the consequences of a particular policy will be (no matter what empirical evidence is available). Instead, they argue that policymakers must find ways of framing policy so that affirm the values of diverse cultural worldviews simultaneously.

As an example, for gun control, they suggest offering a bounty (e.g. a tax rebate) for people who register handguns. Both pro- and anti- gun control groups might view this as beneficial to them, even though they disagree on the nature of the problem. For climate change, the equivalent policy prescriptions include tradeable emissions permits (which appeal to individualists and hierarchists), and more nuclear power (which egalitarians and hierarchists tend to view as less risky when presented as a solution to global warming).

Update: There’s a very good opinion piece by Kahan in the January 21, 2010 issue of Nature.

I think one important reason is that the public doesn’t no longer trusts scientists, and with good reason—think of how many times talking heads with PhD’s have lied for hire in the past four decades about tobacco, pollutants, the side effects of drugs…

Yeah, that’s partly the thesis of Chris Mooney’s new book, “Unscientific America” – specifically that scientists themselves are partly to blame (although he puts it down to poor communication, rather than corruption). But I think that’s the symptom rather than the cause. If you have a situation in which people filter hard evidence according to their worldview, you create an environment in which people (sometimes with phds) are rewarded for telling pleasant lies to those with power and influence. I don’t believe the scientific community can be blamed for this, except perhaps for the failure to teach scientific thinking (as opposed to science trivia) in schools.

It is interesting to see this in actual published research, but is it new? I mean, from Galileo, to Darwin, to Kinsey and even to …”bourgeois pseudoscience“, scientific discovery has never been entirely a-political, has it?

However, I think that there might be a glitch in the method the researchers used: their categorisation of political opinions is static (and that I think is also reflected in the term “cultural worldview” that you use, which sounds rather immutable). But isn’t it reasonable to assume that political shifts happen in individuals when they encounter data they didn’t know, even if that data is indeed filtered by their prejudices? And with regard to policy making, don’t political decisions also impact and reframe political attitudes (“Nixon goes to China”)?

I think that framing policies to appeal to many (possibly opposing) orientations can only have limited success because it’s almost the obverse of detaching it from ideology, it’s over-attaching to many ideologies. IMHO this is a political struggle and at some point there will have to be a winning side…

Sure, people can change their worldview when faced with new data. But the studies in the cultural cognition project suggest that far more often people tend to reject the new data rather than shift their worldview. There’s another whole body of work on diffusion of innovation (ideas) which shows that the dominant factor is what your peers think and do. The people you hang out with tend to share your worldview. When an entire social group does the cultural cognition thing, they all become resistant to change, and the shared cultural worldview becomes entrenched.

We should remember the other half to the Dunning-Kruger tragedy. Competence tends toward reticence.

Wikipedia says:

It also explains why competence may weaken the projection of confidence because competent individuals falsely assume others are of equivalent understanding. “Thus, the miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others.”

Climate science has been far too tolerant of the drooling idiocy mislabeled as skepticism.

Yes they do – and alarmists, including *many* scientists in the Climate community (Hansen is the most conspicuous) do this as well. In fact I’m simply floored that you don’t seem to see this glaring and obvious challenge to modern science where clearly you do see it with respect to the “denialists”, a term that already suggests your own blinders.

[I’ve read many of Hansen’s papers, and see no evidence of him cherry picking data to support a conclusion. Indeed, given Hansen’s prominence in the community, he’d never get away with it. If he’s guilty of ignoring evidence, where are the peer-reviewed papers that challenge his work? Where is the follow up correspondence pointing out the flaws in his methodology? Oh sure, there’s a load of pseudo-scientific crap attacking him in the blogosphere, but if there are genuine scientific objections to his methodology, where is it getting published? – Steve]

I’m fairly well versed in the research and have a fairly strong background in sciences and I’m increasingly skeptical that the models reflect the world accurately enough to justify the level of alarmism. Given the complexity of the statistics, lag times, and non-falsifiability of the models it’s also clear to me that no responsible party should be insisting that AGW is off the debate table. Based on my take AGW is, as IPCC suggests “likely”, but it’s also clear that the most recent IPCC activities have at least been mildly compromised by politics.

[I’ve spend the last year researching exactly this question. I started out expecting the model software to be poor quality, buggy code, and the development processes to be shoddy. I expected to see confirmation bias everywhere, and serious flaws in the validation process. In fact, I found quite the opposite – the climate science community has developed one of the most sophisticated software validation processes in the world. I’d rate it as better V&V than the process NASA uses for it’s manned space vehicles (which I worked on in an earlier part of my career). So, don’t give me that ignorant claptrap about the models being “non-falsifiable”. You don’t know what you’re talking about – Steve]

If you *really* want a good social science research project I think you should stop hounding the ignorance of some of the nonsense skeptic talking points and start looking at how high functioning legitimate scientists have compromised their objectivity in the name of advocacy. I’m very interested in this topic and would be glad to work to help identify a good methodology for this. One I’m pondering now is the idea of examining corrections to data sets in peer reviewed and published reports about controversial topics (like climate) vs non-controversial topics. I think one would expect data corrections to be neutral with respect to the conclusions of the paper. It would seem to me that if advocacy is playing a role (even a subconscious role), one would expect data correction to “favor” the paper’s conclusion, esp. in contentious issues.

[Sure, go ahead. It’s a bit of a crummy research question though, because you have no evidence a priori (apart from your obvious bias against climate science) to suspect there is a systematic problem in corrections of datasets. So what you’re really looking for is evidence to back up your wishful thinking. Setting out to study a phenomena for which there is absolutely no a priori evidence is a pretty crummy way to do research. If you were one of my students, I would advise you to pick a topic for which there is some existing evidence of a problem. Otherwise you’re almost certainly wasting your time. But then, you don’t seem to be interested in doing scientific research anyway. You seem to want to shore up your belief system. – Steve]

Not at all a fair characterization in my view, but hey, it’s your blog and I’ll just pull out a little more hair looking for an unbiased research approach.

[If by “unbiased” you mean “unswayed by the evidence”, then what you’re looking for is not science. Think about it. There are two possible reasons that climate scientists are convinced climate change is a serious problem: (1) because there is overwhelming evidence or (2) because they’re all engaged in a mass conspiracy. Would you describe most physicists as biased because they think gravity is real? – Steve]

So from a research point of view you are suggesting that my question is “crummy” because although cognitive bias clearly abounds in the skeptic community

there is absolutely no reason to suspect we might find any biases within the climate science community? Are you familiar with the Wegman report? It was a very well documented critique of objectivity in climate science but was not peer reviewed. That report alone suggests that at least a bit more research on the topic of objectivity in climate science is called for.

Since several folks in the field (e.g. Lindzen, Pielke, Landsea, etc, etc) and millions of regular folks appear to have concerns about objectivity in climate science isn’t it of some value to at least put these concerns to rest?

[Of course there are biases among climate scientists. The question is, where is the evidence that any such biases have affected their research findings. Wegman didn’t study cognitive biases across the community, he studied the statistical methods used in one particular temperature reconstruction. When you have some credible evidence that an entire scientific community is getting their science wrong, then it will be worth investigating. Without that, you’re playing a political game, not a scientific study – Steve]

It’s always hard to respond to this kind of comment because it’s just an angry retort to the obvious defects in climate modelling. The models are not falsifiable and the justifications for that are dubious in the view of at least a small number of respectable scientists.

In terms of software validation I don’t doubt your findings but also did not realize this aspect of climate science was getting much criticism.

[It’s hard to respond to because you don’t know much about it. I used the term “ignorant” in its technical sense. You don’t seem to know anything at all about how climate models are constructed and validated, but you’re quite happy to go around asserting that they must be wrong. That’s ignorance and arrogance. And you’re accusing climate scientists of bias? Ha! – Steve]

In terms of Hansen it’s not his data that is questionable, rather the speculative conclusions he draws that suggest catastrophes are looming all around us.

[If his conclusions follow from his study, he should just shut up about them? Okay, that’s enough of this. If you want to go on repeating political talking points, find another blog to do it on – Steve]

Oops, hr, ol, ul don’t work. Again:

Part 1. What capabilities would you add to WordPress in view of exp to date? Why?

From a contributor’s p.o.v., I’d want , e.g.,

==The option to contact one another (or block) off-blog – common interests, privacy

==Ability to edit own text – not run to SmE w/ please! and sorry!

==Ability to delete own text – a measure of ownership (UNLESS u accept to give it up)

==SmE’s explicit rules

————————————————————————

From SwE SmE’s p.o.v.???

==

==

==

==

————————————————————————

————————————————————————

Part 2. I zoom in on humans and how they interact in different contexts and power/epistemic/axiological structures. So, I drew up a little ontology of sets of human agents: (phil sense, not compu)

1. denialists => with UNscientific axiology, whether w/ or w/o (clim.) sci degrees

2. deniers => scientists (climatologists or other clued-in experts)

3. deniers => NONscientists & non-climatologist sci’s [misinformed, contrary, “*** says so”]

4. neutralists => GW innocents or socially inactive – period.

5. GW supporters => not devoted to AGW specifically, keeping options open

6. AGW supporters => purists now and forever – Ice Age too close for changes

7. AGW supporters => purists re now but allow possibility of additional robust factor(s), at least hypothetically, possibly due to data misinterpretation or inaccessibility…

————————————————————————

My Qs:

== Which of 1.-7. do you see yourself working with, trying to awaken convert, (whether) failing or succeeding?

== What’s your motivation?

== Who will do what you won’t/can’t?

== Through what medium?

————————————————————————

Which of 1.-7. would be involved in fulfilling 1-4 in your stated interests?

1. comparing and merging views of different stakeholders

2. communicating key ideas about systems

3. how human activities and software systems co-evolve

4. requirements for complex software-intensive systems

————————————————————————

Which of 1.-7. would you care to have on Serendipity? For what purpose, with what expected result?

1. denialists => with UNscientific axiology, whether w/ or w/o (clim.) sci degrees

2. deniers => scientists (climatologists or other clued-in experts)

3. deniers => NONscientists & non-climatologist sci’s [misinformed, contrary, “*** says so”]

4. neutralists => GW innocents or socially inactive – period.

5. GW supporters => not devoted to AGW specifically, keeping options open

6. AGW supporters => purists now and forever – Ice Age too close for changes

7. AGW supporters => purists re now but allow possibility of additional robust factor(s), at least hypothetically, possibly due to data misinterpretation or inaccessibility…

————————————————————————

AT THE END OF THE EXERCISE:

Would you care to spell out what you need Serendipity for in a few points and refer any potential contributor to them before they go ahead and post?

Hey, what the heck – complete the questionnaire above & post for reference (t.i.ch.) Sure, modify to your taste/needs

********** no © !!! :)**********

————————————————————————

————————————————————————

[Lynne: Gotta think about this. will maybe reply in a few days – Steve]

THANKS for Aug 6th post Comment #9

[Lynne: Gotta think about this. will maybe reply in a few days – Steve]

by ALL means, when u get a breather!

I’d say make the Blog Rules and Blog Roles public – for the sake of responsibility, as much as for credit earned. UofT, and even more so CSD, are highly visible, as both our sides know all too well.

Potentially ANYthing on the blog can appear elsewhere as “Compu Prof. Steve Easterbrook says”. Also, wouldn’t it be kinda nice (label it politically correct) for blog contributors as well as any number/type of visitors to know they are talking to/reading Steve (current assumption)? Or a “steve”? Whatever the case may be, why not let young colleagues/grad Ss have their names out there as well – might help Deweyan Growth better than having to emulate – at whatever stage of moderation – an intimidating Ha! mentor, likely t.i.ch., at times at least?

Targetted Audience: Maybe it’s “just me” & some others I referred to S/y…

Or maybe it can really be useful to include HowTo’s that u guys take for granted, e.g., What tags can WPress use? Is it Your choice or WordPress’s (or how you’ve tweaked it) how long to keep a submission pending (& visible) to its author, whether to restore a partial/complete deletion. Is editing in submission window a prob?… Maybe grandma-test Ss on campus (mayhap a worthy MSc project)? Accommodate a general audience (yep: “ugh!” – but cf. steve-note in freshly resurrected #27, Nov26),

OR you can honestly say: If you’re as compu ignorant as to have claptrap Qs such as [quote above] don’t even think of pressing the Submit button – frankly, u don’t belong anywhere near this site.

SLAPJACK MOMENT (I’m only half-laughing):

“UofT Hi&Mitie Prof Blogs You’re Not Welcome Here!

With admissions deadlines approaching, a growing number of high school and master’s graduates are sweating out their choice of a university (under)grad program, browsing websites around the clock for any bit of info that might tip the scales. Will UofT’s Computer Sci Department hold its lead this year, to the chagrin of…? [you continue]”

[Lynne: couple of things: I’ve added a preview button below the comment post so you can see how it will look before posting. But do please cut back on the meta- notes in your comments – it’s hard for me to go through them and find the bits you don’t mean to appear. There is no team, just me – my students all have their own blogs – Steve]

Steve,

TO ELABORATE: whatever I “submit” is wholly meta-blog (before and after I landed here, in Aug 6th), so meta tags are irrelevant – go with whatever is operative for you: publish whole, in part, zero. I keep copies of text submissions and I am looking for answers from *you*, if you would provide them. And am invisible to the rest of the actors. S/y just happens to be the only medium through which I’ve been able to reach you.

How about you think of today’s 2 texts as covering at least ONE WEEK FROM NOW ON? Makes no sense to me to chop up what logically/rhetorically makes connected discourse.

PLEASE CONSIDER #11 an oldfashioned letter, not a blog comment.

Meaning, take as long as you wish to read/reply. If Ever!

Should you choose to read/reply, do it in steps or in one go – whatever.

My area is humanities, not computers. So, I operate on a gradient, not binary code, Black/White. Not saying you’re a binarian – not by a long short – just that what’s good manners and efficiency for you may be close to epistemically vacuous for me.

I need communication of content & situatedness not speed and compression, especially if I’m trying to study the dimensions of perception and affect.

I suspect you read books, if you write them? & newspapers?… Safe to assume skills are transferable?

Well, this one wasn’t as funny, nor did it reduce the length of its sibling, but

:)so be it 🙂

oh, showed colour coding at this point is no go, as well.

sharing notes: Mon Dec 7, CBC radio, messy political side

Part 1. News from Copenhagen

[can’t vouch for precision, but for sure: signif. difference b/n prof Dimitrov’s angle (direct, pic of event didn’t sound “photoshopped”) and Tom Perry’s (possibly “massaged”)]

Andy Barry before 7 am: interview w/ Radoslav Dimitrov, prof of Political Sci, U of Western Ont (??? former UN rep or sth)

He says: Canada = #1 blacksheep – target of NGOs, criticized by China, even small countries for

1) lack of ambition

2) very low-level commitment to policy implementation

comparison: until 2020

Canada commits to 3%!!! decrease in emissions (USA, if I got that right, as bad)

Norway – 40% (similar geography, pop. to Cnd etc.), Russia 25%, Japan 20%

at Kyoto we committed to 6% reductions, but allowed increase

comment by???

East Anglia emails meant to discretid UN effort – but Copenhagen proceeds regardless

7am news: coverage from Copenhagen by Tom Perry

Canada looks “not so good” – not worse

Canada “#1 blacksheep” – but of “environmentalist mvmts”, not of official representation

heard Cnd 20% (not sure what) – didn’t catch mention of 3% ER

East Anglia emails tagged as illegal (by a delegate?)

8am: Tom Perry

UN plan by 2050 described as [re-phrasing] criticized by many/biz experts??? for being unrealistic

Alberta “tarsans” targeted by enviro org’s – the dirtiest project

no mention of % Cdn commitment

today, Harper pitching Korea – for more business to Canada

[me: if Harper’s not in Copenhagen (cf. coverage last week: Harper will be there for part of event, ???towards end I think), has Cnd submitted official numbers, will they stay or are they still subject to improvement during negotiations? Is visit to Korea poised to potentially tip scales t/ds more serious em’s decrease?]

8:10: 15 000 delegates < 992 countries @ Copenhagen

Part 2. On THE CURRENT w/ Anna Maria Tremonte

impression that overview gives: Canada is slipping more and more, from leader (1st internat enviro conf 1988 in Toronto per Green Party leader Elizabeth May, Earth Summit Rio de Janeiro Mexico 1992, acc to David McDonald, Malroney Conserv MP at the time) to close to enviro detractor under Harper’s conserv Gov’t.

Interview with Liberal Environment Minister Christine Stewart who signed Kyoto agreement 1989, took 4 yrs to ratify – Gov’t afraid of Alberta oil patch pushback, Quebec situation, provinces afrad of being dictated to

ChrS: We’re the dinosaurs of today compared to Europe; the Alberta tarsans’ project is not viable for Canada; we/they could be doing more solar E research (like Europe – a lot more advanced that way than us)

@Joe Hunkins

so according to your view, the meteorology profession has been taken over by liberals, since 98% of climate scientists are alarmed as hell that the planet is slowly baking due to human action!

You ought to consider basic Bayesian belief updating with priors for deception and the sociology of science as part of your model too. The way to fight this is to be as transparent, honest and accurate as possible (Feynman’s special kind of integrity).

He also studied the citation patterns in the community, and noted how insular they were. He suggested they would benefit from more consultations with statisticians. That’s pretty much what every statistician I’ve every talked to says about any group of engineers / scientists though (and they are probably right).

Pingback: Another cognitive bug: Attempting to correct a misperception often reinforces it | Serendipity

Pingback: Disinformation Works (for receptive audiences) | Serendipity

Thanks, need to read this Chris Mooney’s book, Unscientific America.

Pingback: What is Science Literacy? | Serendipity